This April Fool’s Day it is fitting to write that I have become….. disabled. There, I have written it.

But I cannot easily say this out loud.

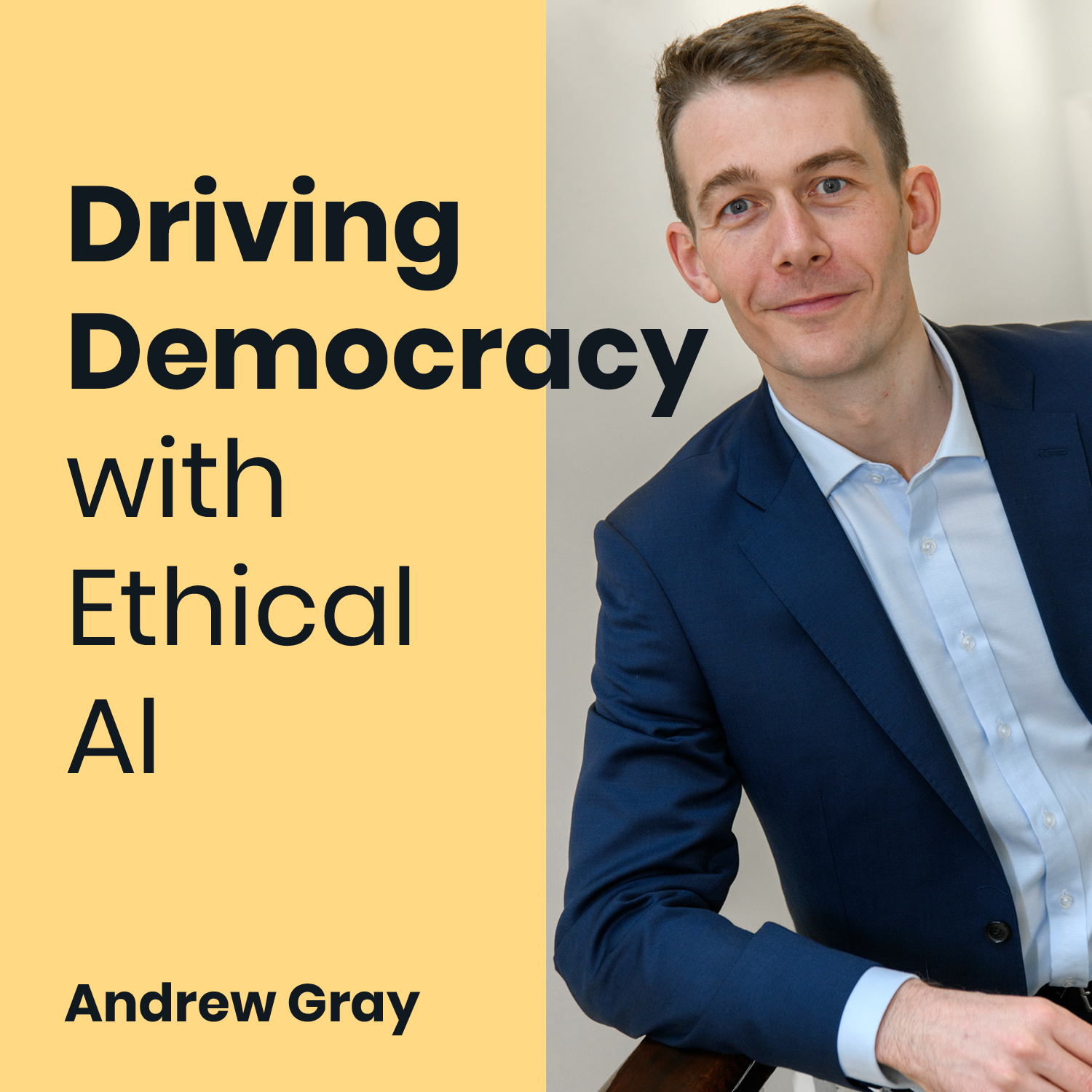

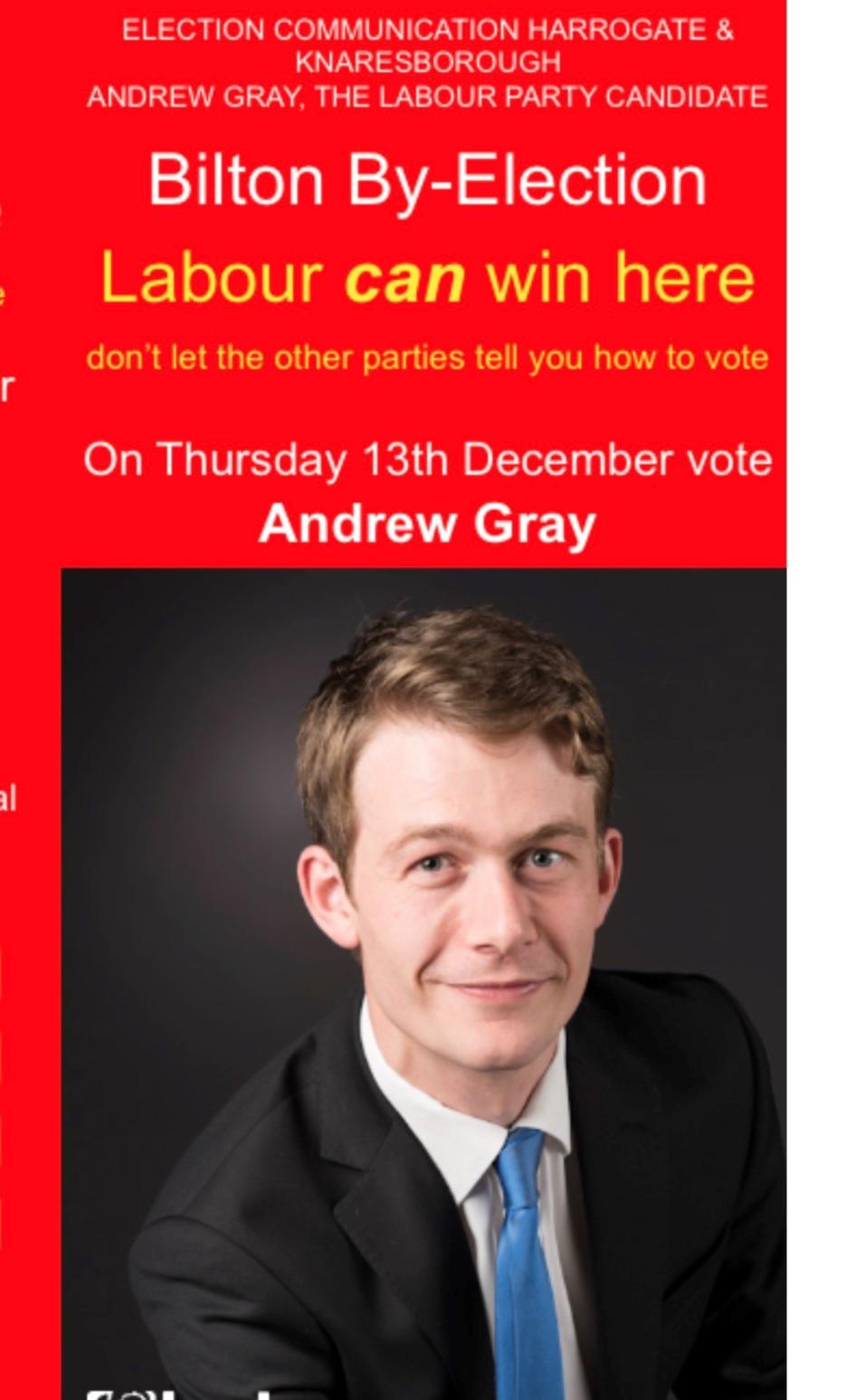

How can I – Andrew Gray – have become disabled? I’ve run two marathons; completed the national Three Peak Challenge; and played competitive football until this time last year. My high fitness levels were always a source of pride. I can tell you how many goals I scored in each competitive season, and for pleasure, I often play back some of the goals in my head. Those were good times.

But this issue – this definition of “disability” – has gnawed away at me over the last few months. In my head, I knew that I needed to write down my thoughts, for in writing I usually find clarity, but I had no prompt. That is, until just now.

Minutes ago, I finished a telephone call with a very good friend, one whom I have played football with countless times. He kindly enquired about how I was doing, without making a big deal about it (which I much prefer). Replying, I struggled to say: “I have fluoroquinolone associated disability. There is nothing that the doctors can do for me.” Ouch. I couldn’t fully finish the sentence. It’s the “D” word which bothers me most.

Perhaps, in my head, disabled people were, I thought, born that way, and have known nothing else. Or, perhaps I thought, that such unfortunate people had suffered a freak accident, leading to their predicament. Of course, I knew that people often become disabled over time – as has happened to me – because I have represented so many of them as their lawyer. Yet, subconsciously, I must have thought that it couldn’t possibly have happened to me. To me! I was fit and able.

In the darkest recesses of my head, “disability” must still have conjured up images of a wheelchair-bound people, even though the legal definition of disability, as set out in section 6 of The Equality Act 2010, has been hardwired into my brain ever since I represented disabled people pursuing disability discrimination claims. It seems that what I knew as a lawyer somehow didn’t connect with what I thought, at a deep, flawed and irrational level.

And yet, possibly, the nomenclature – the terminology, the definition of “disabled” – perhaps is unhelpful. Or just unhelpful to me. In my blog profile, I list all the things that I am, to an outsider, before finishing that “I hate labels”. Does the label – disabled – help me? Does it help others? It must.

And why does it upset me to say out loud: “I am disabled!” I am, in law, disabled. Perhaps I need to own it.

Am I bothered that “I don’t look disabled”? Do I want the condition to be more physically obvious? No, no way, though I am sure that my subconscious craves more obvious signs to the world that I physically struggle: a ready-made excuse as to why I sometimes cannot do something. If I can’t stand up on a train to let a pregnant woman sit down, should I have to explain myself?

Logically, when my day is going well, I must be happy, right? But, then, subconsciously, I feel guilty that I am functioning well. There is guilt in feeling capable, able. And yet there is guilt when feeling incapable, unable.

I suppose that I should make much more of an effort to care even less about what others think. And, I wonder what other prejudices and silliness lurks in my subconscious.